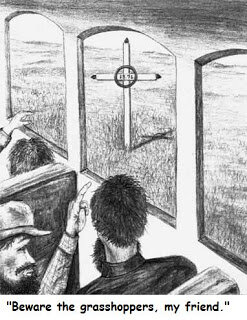

Suddenly, Theo was in Dakota Territory, the southeastern corner of today’s South Dakota. The train had no sooner crossed over the border than it stopped in the little farming town of Jefferson. There, like a powerful guardian spirit, an ominous presence loomed up from nowhere. It was a crude wooden cross, erected in Jefferson’s Catholic cemetery. There was a ring about the intersection of the crossbar and upright shaft like a Celtic cross. It had been erected only two years before—someone pointed out—to commemorate Divine Intervention in the recent grasshopper plagues.

Day and night, above the roar of the train, our ears were kept busy with the incessant chirp of grasshoppers—a noise like the winding up of countless clocks and watches, which began after a while to seem proper to that land.

— (Robert Louis Stevenson, Across the Plains, 1879.)

Yes, Theo had finally entered the gates of Dakota, but this cross seemed to block his way and test his resolve to emigrate west. He couldn’t have failed to hear the story of the grasshoppers. It was a chilling tale of Biblical proportions. . . .

***

It was a peaceful Sunday in early July of 1874 in the quiet town of Jefferson as people emerged from churches with the usual pleasantries. For three years crops had been good and this summer another bountiful harvest was almost certain. The corn was ready and so was the grain.

As they stood in front of their churches or visited on sidewalks, someone looked into the northern sky and saw a dense black cloud. “Just a cloud,” some said. Suddenly a wind sprang up. Then an old farmer recognized the oncoming mass.

“Grasshoppers!” he shouted, “Run for your lives!”

People hurried to their homes, bolted doors, closed windows, and prepared for the most devastating siege known in modern history.

“I remember watching my father go out to our forty-acre field of wheat,” said Mrs. Alfonse La Breche. “Then the sky became dark; it blotted out the sun. Hoppers began falling on the roof and against the windows.

“It sounded like a continuous hailstorm. In one hour the field had been stripped, the heads cut off and the bare stems left standing.

“In the garden everything was taken. Onions and turnips were eaten out of the ground. The hoppers started at the top and worked down; they ate the greens, the bulb, even the roots and left a neat hole in the ground.”

Hoppers covered the earth, buildings, grain, everything. They were six inches deep on the ground. They landed on trees in such numbers they broke branches. All attempts to protect crops failed. The sound of their eating was like a herd of cattle chewing corn.

“We couldn’t keep them out of the house,” said Mrs. Margaret Connors. “They got inside and ate the lace curtains. My brother left a jacket on the fence post, and when he went to get it there was nothing left but the buttons. They would eat the shoes right off your feet.”

Said Mrs. Mary Beaubien: “Our cattle were driven insane by the gnawing of the insects. They tried to run away, but the hoppers were everywhere. My father decided to go after them. He tied ropes around the bottom of his pants and around his sleeves at the wrists. When he came back about an hour later, his clothes were in shreds, almost eaten away. He could not find the animals.

“When there was nothing left for them to eat the hoppers became cannibals and ate each other. They remained about three days then suddenly rose with the wind and were gone.”

The people of Jefferson came out of their homes and surveyed their lands. Destruction was complete. In just three short days, they had been plunged from a good and bountiful life to the prospect of starvation when winter came. Jefferson was not alone in the maelstrom. The invasion extended from North Dakota to Texas and from the Rockies almost to the Mississippi River.

The whole countryside stank with rotting hoppers for more than a week. Many raked them into piles, sprayed them with kerosene, and set them on fire. Some of the farmers pulled up stakes, piled their meager belongings on wagons, and went back to where they came from.

Those who remained, although now in poverty, were a hardy breed and vowed to try again. They stayed for what was later called the winter of corn, flapjacks, and sorghum. The next year (1875) was not much better. Again the hoppers came, but not in such great numbers. Somehow, the settlers managed to survive.

By 1876, the story goes, grasshoppers had nearly eaten out this part of Dakota Territory. Great clouds of them had come—so many the sky turned black; so many that they even stopped the trains. Some homesteaders sold or gave away their claims and went back East. Others left for the newly discovered gold fields in South Dakota’s Black Hills.

The hoppers devoured every green thing that grew, leaving devastation as complete as though fire had passed over the fields. They flew in by the billions and sounded like a rushing storm. There was a deep hush when they dropped to the earth and began to eat the crops. Turkeys and chickens feasted on them and pigs and even dogs learned to eat them. But the grasshoppers ate everything—the corn, the gardens, even the bark off fruit trees. Pioneers threw carpets and rugs on their favorite plants but they ate them, too.

You would think that after they had eaten everything they would fly away. Not at all! They liked the pioneers so well they left their children with them. The mother grasshoppers pierced the earth with holes and filled them with eggs. Each one laid about one hundred eggs. Then they died and the ground was covered with their dead bodies.

It was around this time that the territory declared a day of fasting and prayer. On one muddy Sunday in May 1876, the townspeople and farmers, defeated and despondent, gathered on the grounds of St. Peter’s church in Jefferson and appealed to Father Boucher, South Dakota’s first resident priest, for help. The priest was old and “the snows of many winters had fallen in his white hair.” There was calmness in his voice.

“Have faith,” said Father Boucher. “Do as I ask and the plague will end.”

The desperate farmers said they would do anything he asked them to.

So Father Boucher organized a pilgrimage. Three big wooden crosses were erected that roughly bounded the parish. One was set in the church grounds and two others east and north of town. They called them “grasshopper crosses;” each with a circle in the middle like a Celtic cross. Religious denominations from far and wide came to have a place in the pilgrimage.

Father Boucher, singing litanies, led a mile-long pilgrimage of Catholics and Protestants out into the countryside. They prayed and marched around the whole parish for eleven miles seeking God’s intervention. Women and children rode in wagons; men walked; it was muddy, following a rain. They went first to the cross set in Nelson Montagne’s field, two miles west of Jefferson. Father Boucher conducted a solemn ceremony and eloquently implored divine aid.

So serious and tense was the service that stouthearted muscular men who wrested a living from the earth with their hands—discouraged by gigantic forces with which they could not cope—fell to their knees in the mud of the road and prayed with a fervency they had never felt before.

Then the procession went three miles north to the cross in Moran’s field where another service was held, and back to Jefferson for a final service at the church. The pilgrimage lasted all day.

Joseph Montagne, nephew of one of the founding pioneers, later said: “Hoppers flew over many times after that, but they never landed here again. I have seen them swarm on poles and fence posts without touching the grain only a few feet from them.”

***

So Theo had been warned. He could turn around, get on the next train back to Wells Bridge, and forget the whole thing. Or maybe, past the fiery specter of grasshoppers, there was indeed a bright new future. Perhaps God would continue to intervene and the grasshopper threat would stay away.

The good news was that the hoppers tended to drive down the cost of land. They even threatened to keep the coming railroad out of Sioux Falls:

. . . “if the ‘hoppers don’t come we can afford to haul our grain to where the railroad is now [still miles from Sioux Falls], and if they do come we won’t have any grain to haul, and then we don’t want to pay an extra [railroad] tax.” —(upset farmers, Dakota Pantagraph, Sioux Falls, October 8, 1877.)